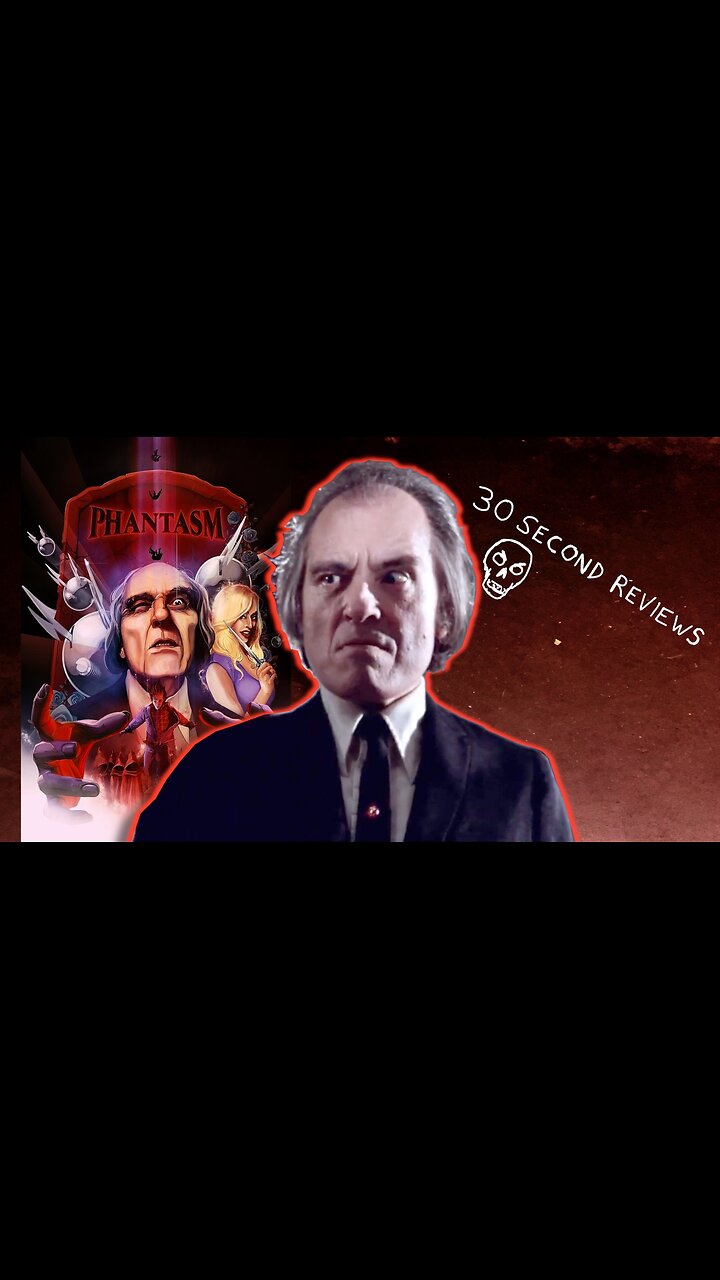

https://rumble.com/v4rlk3w-30-second-reviews-71-phantasm-1979.html #30secondreviews #horror #horrortok #horrormovies #horrorreviews #moviereviews #masterofthemacabre #masterofthemacabrereviews #scifi #horrorcomedy #horrorscifi #horrorrecommendations #phantasm #phantasm1979 #tallman #angusscrimm #doncoscarelli #horrorscficomedy #satire #horrorfilm #horrorfilms #horroranalysis

Circles

Posts

WBIR Channel 10

May 8, 2022

Athens man grows food to deal with inflation prices

Part of Harvey Tallman's setup includes a 1,000-gallon tank with bluegills.

https://youtu.be/aG9MUL7fxoI

Videos

Circles

Videos

Posts

https://rumble.com/v4rlk3w-30-second-reviews-71-phantasm-1979.html #30secondreviews #horror #horrortok #horrormovies #horrorreviews #moviereviews #masterofthemacabre #masterofthemacabrereviews #scifi #horrorcomedy #horrorscifi #horrorrecommendations #phantasm #phantasm1979 #tallman #angusscrimm #doncoscarelli #horrorscficomedy #satire #horrorfilm #horrorfilms #horroranalysis

WBIR Channel 10

May 8, 2022

Athens man grows food to deal with inflation prices

Part of Harvey Tallman's setup includes a 1,000-gallon tank with bluegills.

https://youtu.be/aG9MUL7fxoI